History Is Cool Again

Psst — it always was. Meet MTTR’s historian-in-residence, Jason Steinhauer.

MTTR’s mission of opening minds and fostering deeper understanding of the world and of each other depends on knowing what brought us here in the first place. Unpacking historical context is part of our DNA, which is why we’re psyched to be collaborating with public historian Jason Steinhauer.

Steinhauer has always had a fascination with history. His grandparents were Holocaust survivors, so from a young age he pondered the past and how it shapes who you become. “It instilled in me, even before I could articulate it, just how important history is because it’s from our histories that we derive our identities and our sense of purpose in the world,” he shared.

In this interview, Jason shows us how to go below the surface of common narratives, reveals some ‘secret’ resources for the curious to get lost in, and explains why saying 2020 is the worst year ever is not the best way to think about it.

MTTR: For those of us past our school days, why should we even be thinking about history?

JS: Eric Hobsbawm once said: “We swim in the past as fish do in water. We cannot escape from it.” If you don't know your history, you are a fish out of water. You don't have any sense of where you've been, or why the world around you operates as it does. A critical examination of the past helps to peel back those layers and see elements about our world that maybe we've taken for granted or don't fully understand.

How can we apply history to our everyday lives?

The first thing would just be to ask questions about why. Look in your community and ask why are certain things the way they are?

When you start to ask those questions, you’ll realize that all these things have histories — your street has a history, your house has a history, your community has several histories, your elected officials have histories...When you start to peel back those layers, then it starts to open up a whole new world of understanding about what you're seeing around you.

Pushing on that a bit more, how can we build a better understanding of current issues and each other through history?

Do what historians do and look at sources — primary sources, secondary sources, and start to ask questions and dig into that. With history on the internet, there's so many sources out there now for us to examine a question. Take that curiosity you have about the world and apply it to the past.

You took us on a virtual tour of the Library of Congress archives, which was an incredible resource. What are some other examples of sources you think more people should know?

The Library of Congress is my favorite. Having worked there for seven years, I have a deep affinity for the library, and the depth of the collections is astounding — 175 million items and counting.

There are libraries all across the country and the world that have similar types of collections:

your local library

local historical societies like New-York Historical Society and Historical Society of Pennsylvania

We tend to assume that all of it is online, but there's a lot that's not. Going to those local archives and actually looking at the paper and feeling it in your hands and transporting yourself back to that time and place...there's no experience like it.

I’d also recommend the C-SPAN video library. They've amassed this incredible treasure trove of primary sources, videos of hearings on Capitol Hill, various members of Congress being interviewed, of scholars and journalists and historians and biographers doing book talks. It’s an amazing cache of resources, probably under utilized, and it's all free to search and use.

What kinds of media literacy tools and tips would you recommend people use to judge the accuracy of the historical content they encounter?

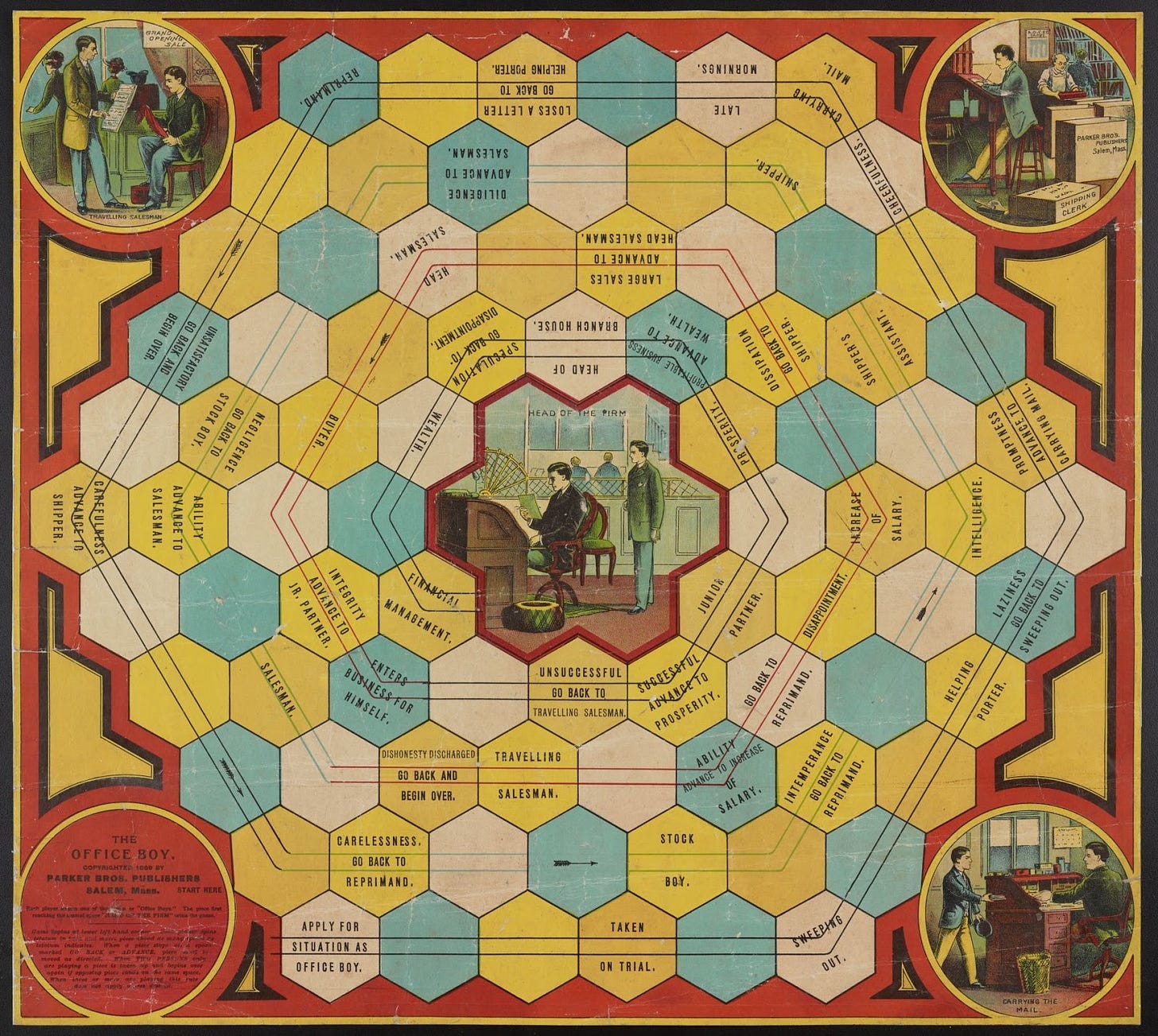

Whether it be a person you're talking to or a piece of information you stumble upon, use the tools of the historian or the scholar: try to understand the source and its agenda. That's really critical. For example, campaigns will create ads, TV spots, rallies...all designed to do certain things. The language, symbolism and imagery are all intended to advance a particular agenda — whether it be to get elected, to lay the groundwork for policy, or any number of things. The same is true with the images we see on our screens trying to sell us a product or make us more aware of a particular product. These messages are not neutral, and it's incumbent upon us to try to dig below the surface and try to figure out what agendas may be at work.

The second thing is to always look at bylines, so understand who has written an article or posted something and try to figure out if that’s someone that you should believe or be a little skeptical of and do more research.

The third is always just to be aware of your own biases. The internet wants to show us things that we will engage with and spend time with, that we will click on to get more of the things we like. Sometimes we have to recognize:

✔ OK, do I need to check myself here?

✔ Have I gone down a little bit of a rabbit hole where I'm just only seeing things that I agree with?

✔ Is it time for me to take a step back and critically assess that I don't have any blindspots in my worldview?

A good way to start uncovering your blindspots is asking questions like, “What am I not thinking about that I could be thinking about? What am I not seeing that maybe I should be seeing? Do I really have the full picture or full understanding of even the community where I live?” And if I don't, “Where can I go to seek out information that would tell me more?”

Jason, we've witnessed you reframing issues before our very eyes — for example, rethinking the expansion West. That was aperture opening to say the least!

There's a whole community of scholars who are re-imagining and questioning the way we tell the American story. If we have an East Coast bias when it comes to American history, do we think about it as moving from the Atlantic coast towards the West Coast in a certain linear progression? And when we do that, are we leaving certain stories out? Are we not telling a more complete picture? It's an interesting thought experiment to flip that on its head and think, OK, what if we start American history, not in the 17th century in Virginia, but in the 16th century, in New Mexico, and think about American history as expanding North and East as opposed to expanding West.

How do you look below the surface of something to think about it in a completely different way like this?

Well, all of this is iterative. So the more you're reading, the more you're engaging, the more you're asking questions, the more it prepares you to do that in different settings...We cultivate those skill sets in younger people when they're in school and then they leave school. Like any skill set it becomes a bit less used. We constantly need to be sharpening and refining that skill set so that we can all participate in that process. If we all participate in that process, then we start to have some really exciting conversations.

What are some pockets of history that you think are vastly under-explored in America?

Good question. There's a lot of local history that still needs to be uncovered and explored — and that goes for people in their own communities. What I mean by that is, as someone who grew up in New York, I know a lot about New York history and American history writ large, but I know very little about Montana history or Nevada history or within indigenous reservations across the United States. And I'm sure that people in those communities could say the same about the communities where I live.

We spend a lot of time wrestling over sort of the meta-narrative of American history and who should be at the center of it and what it means. Sometimes I think that comes at the expense of the local history. There’s a lot to be gained and learned by each of us in our own communities, engaging more with our local histories in addition to our national stories.

How would you describe the state of America today, especially in the last year?

Complicated.

But America has always been complicated, which is one of the reasons why I find it so fascinating. There's jokes among foreign scholars about how young America is, that we don't have as much “history.” But America is so richly fascinating, complex, terrible, and wonderful all at the same time. There is just so much to unpack and dig into. It makes you appreciate that in any given moment, there are tensions and complexities that need to be sorted out. In American history, that’s the norm, not the exception.

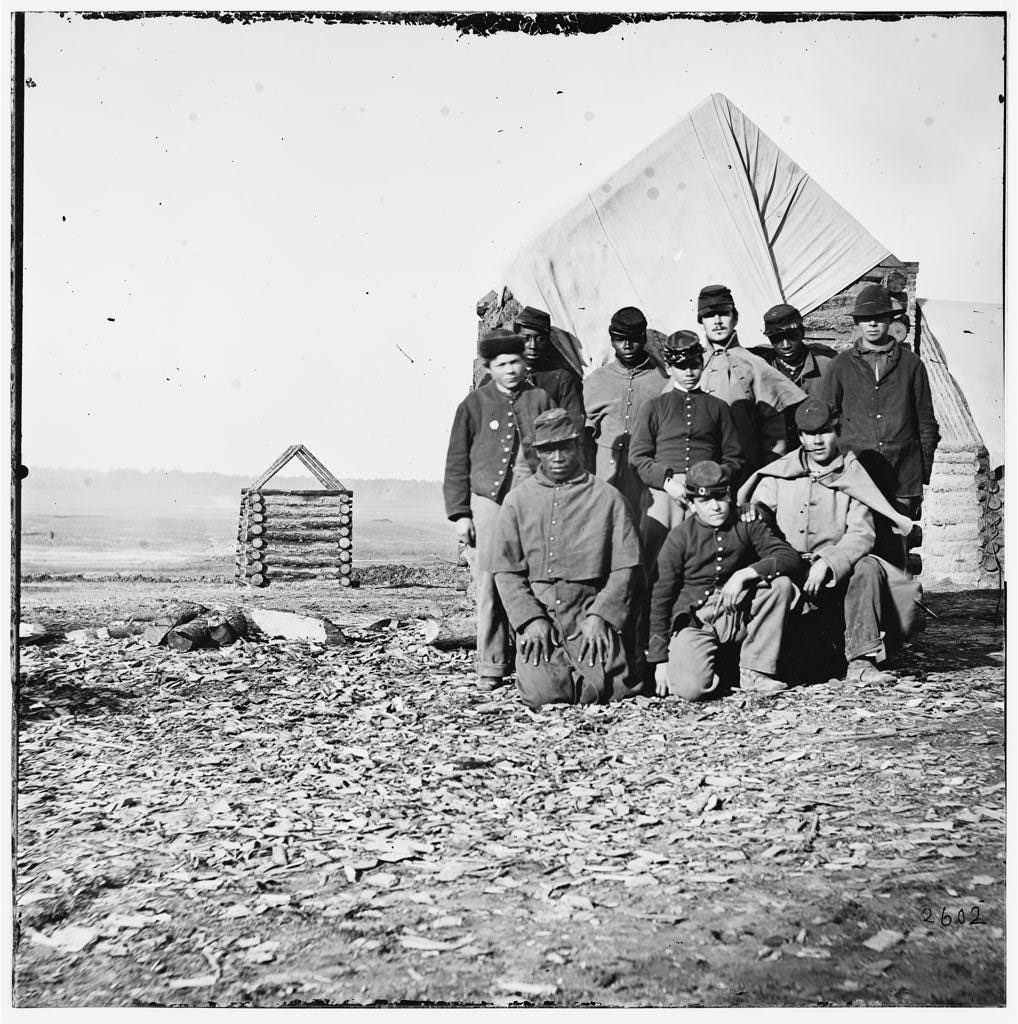

For example, I've always been fascinated by the period in and around the Civil War — the decades leading up to it and the immediate decades after it — because that’s when we see not only some of the promises of America finally being realized, albeit at the cost of terrible bloodshed and suffering, in the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments, but also just how complex the social, economic, and political dynamics were leading up to that war and then as the nation attempted to heal itself from that conflict.

Wars are tremendous moments of rupture but in some cases the periods leading up to and after the war are, to me, more interesting. I'm less interested in, which general led the charge at which particular battle and more interested in how did this really loose configuration of States and territories that was sort of hanging together by a thread for decades finally come unraveled? And then: how did it decide to pick itself back up again, restitch itself back together, and who got included in that process and who got left out?

Let’s zoom back to today — 2020 — what’s been heralded as:

What’s your take on it? Think that’s really true?

I guess I'm just not convinced that's a useful way to think about it — taking a single year and cutting it out of the timeline and holding it up as being more or less anything. History is contingent. The things that happened in 2020 happened as a result of things that happened in 2019, and things that happened in 2019 are a result of things that happened in 2018 and 2015 and 2010, etc.

I'm not sure how useful it is to say like 2020 was the worst year ever, or to compare it to 1918 and ask which was worse. It’s more instructive to look at the underlying phenomena that have gotten us to this point. You could start that exploration in any number of ways. You could start it with the Trump presidency or the state of our healthcare system or the massive inequalities in our society that have been growing exponentially over the past 25, 30 years. In those cases, 2020 would fit into those larger examinations as one point on the timeline.

But is there a historical moment that can illuminate what we’re going through today? Obviously the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic comes to mind.

Again, I'm not convinced that's a particularly useful way to think about it. One of the reasons that we're so captivated by 1918 is because we have a lot of evidence and information about it, but there have been other pandemics in American and global history. You don't even have to go back to 1918. You could look at the 1980s and the AIDS epidemic, how that devastated the United States and around the world.

But we've fixated on 1918. Part of it is that we have really good photographs from 1918 that make for good content that’s gotten circulated by journalists and people on social media. That’s part of what I'm looking at in my book. We tend to pick out certain histories for certain reasons. They get circulated and disseminated online. But how much do they help us actually understand anything? I think that's an open question.

You’re the host of “History Club” on Clubhouse every Thursday night. What have you learned from moderating that experience?

I learned that there is really a thirst and an appetite for historically informed, civic-minded conversation, even around difficult topics where we have disagreements and differing perspectives. It is possible to have a healthy discourse that doesn't shy away from the difficult issues that we need to address, and it can still be done in a constructive way.

Jason Steinhauer served as founding director of the Lepage Center for History in the Public Interest, is a Senior Fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, and is a contributor to CNN and TIME. He is currently writing a book about history on the Internet. You can catch Jason on Clubhouse hosting “History Club” every Thursday night. Follow him on Twitter @JasonSteinhauer.